Part of these notes were published on the book: ‘Five Centuries of Italians in Hong Kong and Macau. 1513 – 2013.’

Demand for Far Easter goods had been insatiable since the time of Julius Caesar. The Roman dictator had been the first to wear a silk toga and gave to his mistress, Servilia, a black pearl from the South Sea that he had paid a fabulous amount of money. In a way he was a fashion trend-setter and many other famous Romans imitated him. As a result Roman silver and gold flew east causing several fiscal crisis. Romans could only export glass, textiles, small metal works to balance the increasing deficit. The problem remain open until a only radical way to balance the budget was found by the British in the XVIII century. They did pay back with opium from India. A combined sea-land trade route to cut out some middlemen was found by Roman merchants in the second century A.D. but then it was abandoned.

There were several embassies sent by Roman emperors. Emperor Nero had always been fascinated by the East and dreamed about retiring there. Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, in order to establish trade relations, sent embassies that reached China.

A thousand years later, because of the Mongols’ domination of most of the known world (they easily defeated Russian, German and Hungarian armies during the months of March and April 1241 and then entered Budapest). With them the gates of China were open and many travellers went East using the overland route. The Mongols captured scores of Christians during their European and Russian raids and appointed Genoese and Venetian traders as their agents for the slave trade. Once the Mongol empire vanished, the Persian and Arabs middlemen came back and prices soared. Demand for spices had always been great in Europe, pepper, nutmeg, cinnamon, liquorice, mustard and indigo and their cost very high. We should not forget drugs, there were several books written during the Renaissance about Chinese medicine and their curative properties, real and imagined. The allure to find a direct way to import them was enormous.

The Italian Renaissance had put into the hearts of the Europeans a new spirit, in their minds new ideas and, in their hands, new maps, new fighting techniques. They were a new kind of people which the imposing civilization of Ming’s China, anchored to an old tributary system, to bureaucratic regulations and very limited foreign contacts, did not know how to tackle. That put China to a great disadvantage.

A large number of Italians disembarked in South China over time: soldiers, sailors and clerics, travelling on their own or at the service of the Portuguese seaborne Empire which at that time was being built at an amazing speed, as C.R. Boxer put it: “It was this misture of deeper passionats-greed, wolfish, inexorable, insatiable, combined with religious passion, harsh, unassailable, death-dedicated that drove the Portuguese remorselessly on.”

In 1459 a Venetian friar, Mauro di San Michele ( ? – 1459) assembled a large parchment map of the world, adding a great number of notes and caveat, he was aided by other cartographers and travellers, like Andrea Bianco and Niccolò de’ Conti. It had been commissioned by King Alfonso V of Portugal. Some suggested that it was from that map the Portuguese got their idea of travel east. A second copy of his huge elliptical world-map, having about two meter in diameter, is kept in the Marciana library of Venice, while the first sent to Portugal has been lost, even if it was recorded until the eighteen century in the Portuguese monastery of Alcobaça.

Andrea Corsali (1487 – ?) remembered today mainly for having been the first traveller to describe – and having sketched – the constellation of the Southern Cross, wrote letters back to Giuliano de’ Medici in 1515 reporting about what the Portuguese were discovering. Corsali knew personally Leonardo da Vinci who, by the way, had a keen interest in the east, much more than in America. The presence of Corsali on a Portuguese vessel seems to point to a direct financial involvement by the House of Medici into the Portuguese venture on what was then known as “the spice route.” The Medici were most probably contributing to the financing that Portuguese explorations.

Corsali, in one of his letters famously said about the Chinese: “They are people of great skill, and on a par with ourselves.”

Giovanni da Empoli (1483 – 1518) a Florentine right hand man of Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque (1453 – 1515 was also impressed by the Chinese he met and said: “They are white, and dress similarly to Germans with kind of French shoes.” He then added that if he will not die too soon he would like to visit China. Giovanni da Empoli was an agent for the Florentine merchants house Gualtierotti & Frescobaldi and perhaps had been the first travelling banker in Asian history. He completed three trips to South-East Asia and joined Admiral Albuquerque’s expedition to Melaka. He was later dispatched to Sumatra. He then spent some time on that island before moving to China, where he reportedly died near Macau in 1518. So, at last his wish had been granted.

The Genoese brothers Ugolino and Vadino Vivaldi (? – 1291) given the impossibility of crossing Arab lands, decided to try sailing East by circumnavigating Africa, anticipating Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese by two centuries. Financed by Genoese merchants and noblemen, they set off in 1291 on two galleys, the Allegranza and the Sant’Antonio, with a crew of three hundred men. They made a stop at Majorca but were last seen along the coast of present-day Morocco; their subsequent fate is unknown. One of the brothers’ sons launched a search expedition but the two adventurers were never found. Subsequently several legends circulated about what may have happened, that was probably the source of inspiration for Dante Alighieri (1265 – 1321) when, in the Canto number XXVI of Hell, wrote about the fate of Ulysses.

Generally speaking Genoese sailors were not as lucky as they should have deserved: Christopher’s Columbus (1451 – 1506) sailed west hoping to get to China but instead struck into America.

Another Genoese, not as famous as the others, was Benedetto Scotto (? – 1640). A bizarre nobleman who wrote a treatise at the beginning of the XVII century in which he claimed that was possible to reach China going through the North Pole and then coming down from Japan.

Scotto mentioned in his book about a Continentis Australe after the Nova Ghinea who in his opinion was full of riches, huge and a sort of Garden of Eden. Information that he may have obtained from Corsali or from other explorers. This book was printed in Antwerp in 1618 and later in France. It seems that his vivid description spurred some to look for Australia, where the first landing was made by the Dutch explorer William Janszoon in 1606, and bolder expeditions were then made by the Dutch in 1623 and 1636.

Another Genovese explorer, named Paolo Centurioni (? – 1525) had proposed a land route to China to Basilius IV, Prince of Moscow (1503 – 1533) with an itinerary similar to the one followed today by the Tran Siberian railway. British King Henry VIII (1491 – 1547) also toyed with this idea, since the maritime route was a Portuguese monopoly, so much so that he invited Paolo Centurioni to London, but unluckily the Genoese got sick and died there.

Vasco Da Gama (1460 – 1524) reached Calicut in 1498 and there heard stories of pale faced, bearded men, travelling on big ships and called Chin. That was probably the lingering impressions left by the fleet of Chinese Admiral Zheng He (1371 – 1433).

Dom Francisco de Almeida (1450 – 1510) had defeated a Muslim fleet at Diu, on 3rd of February, 1509 on the west coast of India. The Venetian were allied of the Arabs and the Persians because they were losing their monopoly to the Portuguese, that were cutting out all the middlemen. The Mameluks, with technical assistance from the Venetians, had disassembled ships in Alexandria of Egypt and reassembled them on the Red Sea to move against the Portuguese, but their superiority in guns and seamanship made the difference. That was the beginning of an annus horribilis for Venice. The League of Cambrai composed by all the European powers with the exception of England and Hungary took arms against them and invaded Venetian territory. During the spring of 1509 a mainly French army invaded their territory and on 14th May 1509 defeated a Venetian mercenary force. That was the end for the Republic of San Mark. They lost the cities of Bergamo, Brescia, Verona Vicenza and Padua. Their conquests of eight centuries were lost in a single day, as a gloating Nicolò Machiavelli noted.

The first Portuguese and Chinese ships met in Melaka in 1511. Visiting Arab merchants, who saw their trade in grave danger and jealous of the newly arrived, convinced the Sultan of Melaka to attack them. Many were killed or captured but some escaped and the new viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque (1453 – 1515) returned with 18 warships and declined the offer by the Chinese merchants to assist him, he stormed the fortress and took possession of the city.

Ludovico di Varthema (1470 – 1517) was born in Bologna. Thirsting for adventure, he left Venice in 1502 for a distant journey to Siam, present-day Thailand, and Malaysia, enrolling in the Portuguese garrison as an officer. He was later knighted by Admiral Francisco D’Almeida. On his wonderful journey, which he described in his book Itinerario de Ludovico di Varthema, Bolognese published in Rome in 1510, describe all his travels from the Holy Land to the Far East. During a part of his trip from Chittagong he was together with a Persian and two Chinese Christians, probably Nestorians. He staid in Java and Melaka, and he further reported that at Calicut he met two skilful gunners from Milan, deserters of the Portuguese at the service of the local king. An earlier case of technology transfer…it was the month of August 1505. Here is the chapter of his book, in the vivid translation made by John Winter Jones in 1863:

Being then arrived in Calicut on our return, as I have shortly before written, we found two Christians who were Milanese. One was called Ioan-Maria, and the other Pietro Antonio, who had arrived from Portugal with the ships of the Portuguese, and had come to purchase jewels on the part of the king. And when they had arrived in Cochin they fled to Calicut. Truly I had never had greater pleasure than in seeing these two Christians. They and I went naked after the custom of the country. I asked them if they were Christians. Ioan-Maria answered: “Yes, truly we are.” And then Pietro Antonio asked me if I was a Christian. I answered: “Yes, God be praised.” Then he took me by the hand, and led me into his house. And when we had arrived at the house, we began to embrace and kiss each other, and to weep. Truly, I could not speak like a Christian: it appeared as though my tongue was large and hampered, for I had been four years without speaking with Christians. The night following I remained with them; and neither of them, not could I, either eat or sleep for the great joy we had. You may imagine that we could have wished that that night might have lasted for a year, that we may talk together with various things, amongst which I asked them if they were friends of the king of Calicut. They replied that they were his chief men, and they spoke with him every day. I asked them also what their intention was. They told me that they would willing have returned to their country, but they did not know by what way. I answered them: “Return by the way you came.” They say that was not possible, because they had escaped from the Portuguese, and that the King of Calicut had obliged them to make a great quantity of artillery against their will, and on this account they did not wish to return to that route; and they said that they expected the fleet of the King of Portugal very soon. I answered them, that if God granted me so much grace that I might be able to escape to Cananor when the fleet had arrived, I would so act that the captain of the Christians should pardon them; and I told them that it was not possible to for them to escape by any other way, because it was known through many nations that they made artillery. And many kings had wished to have them into their hands on account of their skill, and therefore it was not possible to escape in any other manner. And you must know that they had made between four and five hundred pieces of ordnance large and small, so that they had great fear of the Portuguese; and in truth there was reason to be afraid, for they not only did make the artillery themselves but they thought the pagans to make it; they told me moreover, that they had also thought fifteen servants of the king to fire spingarde. And during the time I was here, they gave to a pagan the design and form of a mortar, which weighted one hundred and five cantara and was made of metal. There was also a Jew here who had built a beautiful galley, and had made four mortars of iron. The said Jew going to wash himself in a pond of water was drowned. Let us return to the said Christians: God knows what I said to them, exhorting them not to commit such an act against Christians. Piero Antonio wept incessantly, and Joan Maria said it was the same to him whether he died in Calicut or in Rome and that God had ordained what was to be.

Very little is known of those first contacts. Few written reports are available and all are incomplete. The first European to actually land on the Chinese Continent was perhaps Admiral Raffaele Perestrello in 1515. His family originated from the Italian city of Piacenza. Raffaele Perestrello was dispatched from India to secure trading relations with the Chinese. He then used a ship sailing from Melaka, landing on the southern shores of Guangdong; he traded some goods and then left. He made a further trip to China in 1517. His ancestor, Filippone Perestrello, moved to Portugal in 1385 with his wife, Catherine Sforza, they lived in Porto and then in Lisbon. Filipa Moniz Perestrello, cousin of Perestrello, married Christopher Columbus. Perestrello had already proven his ability to conduct commercial expeditions by sailing to the Andaman Islands of Bengal, Sumatra and Melaka, always serving as captain under the Portuguese Admiral Afonso de Albuquerque. In fact, his glowing reports on the potentiality of trade with China’s, were the main cause that motivated Tomé Pires (1465 – 1524?) and Fernão Peres de Andreade (? – 1523) to carry out a diplomatic missions to China. Despite the tragic failure of their diplomatic endeavour, in 1521 and 1522 the Portuguese traders obtained the right to anchor ships in Tuen Mun (now within Hong Kong’s territory) and Macau, a small peninsula where the Portuguese settled in 1535, and received official permission of residence from the Chinese authorities in 1557.

Portuguese captain Jorge Álvares (? – 1521) was the first European to land on a Chinese island where on a chartered Burmese vessel disembarked on Lintin Island in May 1513. Others, like the Polo family, had left but not arrived through the South China sea.

That is a large island known today as Nei Lingting, it is very close to Hong Kong but under the prefecture of Zhuhai. For the best view of it we should hike up to the top of Castle Peak in the New Territories. Some Italians may have been there with him. In 1514 again he landed at Tuen Mun, which is today part of Hong Kong. In 1517 he went up to Guangzhou where he made a great gaffe by firing cannon shot when he dropped anchor in the port. The Chinese were outraged by such effrontery. He explained that it was just a salute and that he had seen Chinese ships in Melaka doing the same. This explanation further worried the local authorities, because private trade had been absolutely forbidden by the Ming emperor, even if it was illegally flourishing. Further to this, the Sultan of Melaka, who the Portuguese had deposed, was actually a loyal Ming tributary. The Ming had long abandoned control of the sea and this can explain why the Portuguese were able to fill the vacuum so easily.

Francesco Carletti (1573 – 1636) and his father, Antonio, disembarked in Macau from Japan in 1598. They were also from Florence and Francesco is remembered as the first man who travelled around the world by securing his passages as needed. While in Macau, the two men encountered the Jesuit Alessandro Valignano. Francesco’s father fell ill, died and was buried in Macau but to raise his sinking spirits Francesco had an unexpected encounter with an old childhood friend from Florence: Orazio Neretti, whom Francesco happened to spot disembarking from a ship coming from Goa. Neretti had missed his connecting ship to Japan. A stroke of luck because that ship, with her cargo of porcelain, silk and tea, with her entire crew disappeared without a trace.

In 1695, during a pleasure trip around the world, Giovanni Francesco Gemelli Careri (1651 – 1725) a Neapolitan nobleman, also sailed through Macau. Upon his return to Naples in 1700, he published his diaries, which recounted his journeys around the world.

Gemelli Careri has been cited by some as the first real tourist visiting Asia because his travels were not driven by commercial, religious, diplomatic or military goals. A full two chapters of his books focused on the history and commerce in Macau. It is believed that the Jesuits suspected him of being a popish spy, secretly sent by the Pope, and thus they did everything in their power to please him. They escorted him to Beijing introducing him to Emperor Kangxi, even allowing him to tour the Great Wall and other monuments. While in Beijing, Gemelli Careri saw a number of Chinese maps, erroneously contributing to the legend that Matteo Ricci had put China at the centre of the world. Gemelli Careri’s diaries were greatly influential in his time and, one hundred and fifty years later, inspired Jules Verne in his Around the World in Eighty Days. Below is an entry from his Macau journal, dated 9 August 1695:

I went to see a play acted upon after the Chinese manner, it was represented at the cost of some of the neighbours for their diversion in the middle of a small square. There was a large stage to contain 30 persons, men and women actors, and I understand it not, because they spoke mandarin, a Court language, yet I perceived the manner of it, and that they acted a lively manner and with great skill. It was partly recited and partly sung, the music of several instruments of wood and brass harmoniously answered the voice of the singer. They were all well enough clad, their garments adorned with gold, which they changed often. The play lasted 10 hours, ending by candle light. When an act is done, the players sit down to eat, and very often the audience does the same.

In 1784, Tuscan Admiral Alessandro Malaspina (1754 – 1810) sailed through Macau, commanding the Spanish ship Asunción. He returned to Macau in later years, finally falling into disgrace as a result of conspiracies at the Court of Madrid.

Carlo Vidua (1785 – 1830) was a naturalist, bibliophile and explorer from Casale Monferrato, he visited Macau in 1829, but then tragically died the following year, because of injuries and burns due to his fall into a volcano, in the Indonesian archipelago.

The Birth of Hong Kong in 1841.

The imperial government in Beijing always considered Macau and Hong Kong like periferical extensions of its vast empire. It regarded the two territories as outgrowths of Guangzhou – remote lands, part of the southern border, uncultured and not civilized – but, as such, suitable for maintaining commercial relations with the western barbarians, keeping them at a safe distance in order to avoid contamination. It is no coincidence that one of the two ideograms representing the city of Macau is a door.

Giuseppe Garibaldi reached Hong Kong and Macau in 1852, he was the captain of the Peruvian cargo ship Carmen. A wanted man, he was sailing under the false name of Giuseppe Pane. He shuttled between Macau, Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Xiamen for a few weeks before returning to South America. Nino Bixio, his lieutenant, did not make it to Hong Kong with his beautiful steamship, the Maddaloni. He had intended to establish a trading company in Hong Kong and Singapore, but died of typhoid fever in the Sunda Islands part of the Malay Archipelago before he could carry out his business plan.

When Hong Kong was established, in 1841, almost immediately the core of Europe’s presence in China shifted to the new territory. Macau did not fully recover from that blow.

It was only during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, from late 1941 to 1945, that Macau became again a focal point of relative peace and a sort of safe haven. In fact, despite its reduced size, Macau provided shelter to eight-hundred thousand refugees, including some Italians. At tremendous cost and risk, Portuguese authorities managed to provide enough rice to feed most of them.

While as a country Italy is only twenty years younger than Hong Kong, if one considers Italy as the peninsula where people share a similar language and history, then it can be dated well before Macau’s founding. Italian priests were already in Hong Kong at that time, as it is discussed in a separate chapter of this book.

Vittorio Arminjon, captain of the steam powered frigate Magenta, and the Chinese plenipotentiary appointed by the emperor, Than, signed the treaty in Beijing. It was a major coup for the Italian commander to have placed Italy at the same diplomatic level as countries such as Great Britain and France. This was the beginning of diplomatic ties between the newly founded kingdom of Italy and Imperial China sealed with a treaty dated 26 October 1866, ratified in Italy into Law no. 4406 of 23 May 1868. Article no. 11 in which it is stated that:

In these ports, Italians can trade with anybody, arrive and leave with their goods, build and rent houses, lease lands and build churches, hospitals and burial grounds.

Article no. 54, concerning favoured nations, is also noteworthy:

It is hereby expressly agreed that the Italian Government and its subjects will benefit, with full rights and in equal measure, from all the benefits, immunities and advantages which are, or will be, granted by His Majesty the Emperor of China to the Government and its subjects of any other Nation. Similarly, in the event that any of the European Powers should grant to China any useful concession, which will not be adverse to the interests of the Italian Government or its subjects, the Government of His Majesty the King will endeavour to adhere to the same concession.

The Magenta was on a scientific mission, circumnavigating the globe and on the way back from Beijing casted anchor in Hong Kong. Filippo de Filippi, possibly the most famous Italian naturalist of those days became ill and died in Hong Kong in January 1867. De Filippi, a native of Milan but teaching in Turin, introduced Darwinism to Italy, he was buried in the Catholic cemetery of Happy Valley, but his mortal remains were subsequently transferred back to Pisa, in Italy, where his daughter was living.

De Filippi’s assistant, professor Enrico Hillery Giglioli, published a diary about the trip titled Viaggio intorno al mondo della Regia Pirocorvetta Magenta. This publication was highly acclaimed. Below is a passage from an entry penned in Hong Kong:

Suddenly we turn over a cape; the channel widens and is filled with hundreds of boats of all shapes and sizes. In the background, instead of barren and steep rock, appears a magnificent city, which rises before us at the foot of a high mountain, the shining surfaces of its white buildings reflecting the rays of sun. That marvellous sight was Victoria, better known as Hong-Kong, the island’s real name. The Magenta reduces its speed and weaves its way through junks and boats; it arrives at the place reserved to warships and drops anchor not far from land, in front of the army dockyard. Completed the salute, we can finally admire Victoria’s breathtaking landscape; this city is reminiscent of Genoa, and vaguely of Gibraltar, as it unfolds like an amphitheatre over a sheer cliff, overlooking the sea. In front of us soars the city’s homonymous peak, its signal light – indicating arrivals and departures – placed at its summit, 555 meters above sea level. The mountain’s slopes are not bare: houses stretch along its base and over the conical hills surrounding it.

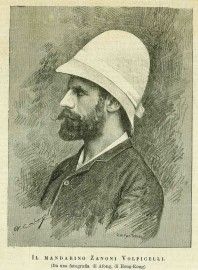

Tuscany was the birthplace of many renowned orientalists who then landed on the shores of Hong Kong: Antelmo Severini, Carlo Valenziani, Ludovico Nocentini, Carlo Puini. The Neapolitan Eugenio Zanoni Volpicelli was one was the best Italian Consuls in Hong Kong and Macau between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was the author of several books on the China-Japan war and Chinese phonetics, history and gepolitic English. Domenico Antonio Mazzolani in his book Verso la Cina, published in 1915, portraits Volpicelli with these words:

I arrive at Commander Volpicelli’s office just after ten. He is surprised to see me again; he enquires about Libya and, more specifically, about war. He says that our conquest has had very positive effects even in China, although our local commercial interests risk worsening.

According to Mazzolani, Volpicelli regrets that Italian steamships are no longer docking in Hong Kong.

Consul Volpicelli is a dangerous man from a doctor’s point of view; you need to remain constantly on the alert with him. He is a health fanatic and his reasoning requires attention. Every morning, he walks down from his house, situated almost at the top of the Peak. This daily routine and an almost vegetarian diet give him a physical agility rare for his age. Finally, we talk about our business. At that moment, his attendant brings him a business card: is Baron La Penna, Ambassador of Italy in Bangkok, heading to Japan. The Consul rises to meet him; it seems that the former has encountered some difficulties in finding the Consulate. The emblem is rather small and worn out but, thank heaven for our tricolour flag, which always saves the day.

In the early twentieth century, an Italian Far East Trading Company, owned by Giulio Badolo, was operating in Hong Kong. In 1900, Luigi Barzini (1874 – 1947) landed in Hong Kong enroute to Beijing, where he was going to report on the Boxer uprising. Italy had joined the fighting and sent three thousand and six hundred soldiers and seven warships. His articles were later collected into a book that went through several editions and that remains up to this day the most humane and accurate reporting on that terrible tragedy.

Barzini reported that there were twelve Italian residents in Hong Kong at that time, and then went to present his greetings to the Italian Consul, Commander Volpicelli. On 14 August 1900, Barzini reports the following, in his characteristically picturesque style.

Raising my eyes from my writing, through the open window I admire one of the most beautiful landscape human eyes could ever behold.

If what poets want us to believe – that is, that beauty has the power to inspire – is indeed true, I should be writing this letter in superhuman verses. Instead, my sole inspiration is to discard pen and paper, and lose myself completely in the most foolish – and hence, sweetest – of the contemplations: a selfless, empty contemplation. The hotel where I am currently staying is situated at the top of the Hong Kong Peak.

Hong Kong is built on an island, which, like all small islands situated in this corner of the world, consists in a single, steep and rocky mountain. At its feet, on the northern shores, lies the city. The mountain peak is Hong Kong’s Garden of Eden; up here, in this delightful retreat, Europeans come to nest, high above and far away from the heat and stench of the coast. Here, the mansions and hotels, form a separate hamlet, lush and immersed in greenery. The rock was transformed into a garden, with boulevards winding amongst meadows in bloom and bamboo and aloe bushes, and avenues cutting trough the pinkish rock, which resemble long, bleeding wounds.

All around, the sea opens below, the jagged coastline toothed by rocks, islets, peninsulas, like a Norwegian sea – a full scale geographical map, where only the meridians and latitudes are lacking. Indeed at sunset: the time of day that turns sailors soft-hearted. Since yesterday, however, I am no longer a seafarer, and hence feel nothing in my pericardium.

The route that brought me here is now lost before me, far away, to the south, in fiery mists. A large herd of islands raises the backs of a calm sea, glowing pink. They stand out like pieces of an endless setting; the closest are blue, then, further away, they become violet and grey and, finally, carnation pink. Several bizarre clouds light up at sunset: thin and straight strips of fire, they are the Archangels’ blazing swords, extended over the horizon. The wind traces ever-changing lines of cobalt on the sea’s surface. In the distance, a few streaks of smoke – a steamship – appear to float in the light. Near the coast, several sampans, their yellow sails reminiscent of bat’s wings, are approaching the bay. Endless peace, solemn silence.

From the other shore, the bay opens up between the island and the continent. China’s mountain ranges disappear in the purple haze. Downhill, in Hong Kong, in the shadow of the great Peak, the night has already fallen and the city starts to fill with lights. A shimmering crown stretches along the bay. On the water, light as air, hundreds of anchored ships, sampans, junks, ferries, steamboats and ferry-boats light their beams, and now reflect upon the calm water in zigzag movements. It seems as though a corner of this beautiful starry sky has fallen into the sea.

I feel suspended in the infinite. The electric lamps of the streets, yards and docks are unmoving stars amongst the softer lights of the windows and the nebula of thousand pale Chinese lanterns lighting the streets. The moving lamps of the rickshaws and of the wooden sedan chairs, born by coolies on their shoulders, remind me of the thousand shining lights that cross a burning piece of paper before it dies out.

This is all sublime, and largely compensates for the bitter disappointment of those who – like me – alighted in this first corner of China, thinking they had truly arrived in China.

Arriving in Hong Kong, after having visited those corners of emigrated China, known as Penang and Singapore, one lives the illusion of having stepped back in time. Just like that famous farmer, who, having bought a return ticket for the first time, he thought he was travelling “backwards” until he found himself back in his home village.

From the sea, Hong Kong resembles Genoa. Rows of European buildings scale the mountain on different levels in an eclectic medley of styles: English, Italian, Gothic and Renaissance; however, not even the slightest hint of an inclined roof or a single pagoda. Chinese architecture is banned.

The magic of Hong Kong must have cast its spell on him too, for he ends his paragraph saying:

The kindness of the people conspires with the divine beauty of the landscape. I must wait a few more days before heading north. Well, for the first time in my life, I find waiting to be a pleasant affair.

Guido Amedeo Vitale, from Tuscany, lived both in Macau and in Hong Kong. During the 55 days of the Boxer Rebellion (20 June–14 August 1900), he was locked inside the diplomatic compounds during the Siege of the International Legations in Beijing. He worked as translator for the Italian Embassy.

In 1910 Mario Appelius (1892 – 1946) from Arezzo disembarked in Hong Kong from Indochina; he had run away from home at the age of fifteen. He tried to earn his living in Hong Kong but was unsuccessful even if later wrote a number of successful books in which he idealized his vagabond life: Da Mozzo a scrittore; Asia gialla: Giava, Borneo, Indocina, Annam, Cambogia, Laos, Tonkino, Macau, Cina; La crisi del Budda and several others. He had a previous, albeit confused, knowledge of China because his grandfather had been a silk trader from Como, one of the first to set up a modern silk factory in Shanghai.

Edda Ciano Mussolini (1910 – 1995) whose husband, Gian Galeazzo Ciano (1903 – 1944) had been appointed Italian Consul in Shanghai between 1930 and 1933, travelled often to Hong Kong. It is reported that her friends obtained military information while playing bridge with the wives of British officials, then reporting them back to Rome. Fuelling the espionage theory, history books mention a certain Gino, habitué pool-player at the Hong Kong Hotel, who was in fact a secret agent working for the Japanese. A friendly Japanese barber working in the same hotel transformed himself into a Japanese captain following the invasion.

The de luxe Italian Ocean liners Conte Rosso and Conte Verde moved passengers between Genoa and Shanghai, going via Singapore and Hong Kong. They were strong competitors of the more basic P&O vessels. Before Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940, the two liners transported thousands of Jews who were fleeing to Shanghai from Europe with false visas to escape the Nazis.

Below is a report issued by the Italian Consulate of Guangzhou in 1941 regarding the situation of Italians living in Hong Kong:

The number of Italian residents is limited. The colony consists in a few food dealers, mosaic design layers and waiters working in hotels. It cannot be described as a wealthy colony, and it has no influence whatsoever on the economic and political life of our host Country. Our Italian missions, on the contrary, hold great power, particularly the Catholic Mission of the Pontifical Institute of Milan, which counts about 30,000 believers, and is led by an Italian Bishop, helped by Canossian Sisters and hard-working Salesians. Italian shipping in Hong Kong ranks only 12th place. Italian exports to Hong Kong exceed imports. Though our trade activity was severely affected by sanctions, it began to recover in 1937. Italian exports consist mostly of fabrics, silks, foodstuff, cement, quicksilver, etc. Based on the effects of the political contingencies on trade relations with foreign countries that China has enforced since 1937, we do not envisage a prosperous future for our trade.

Italian warships often visited the Hong Kong harbour. Italy had obtained concessions in Tianjin and Shanghai and this situation demanded a military presence. The armoured cruisers Trento, and several battleships Colleoni, Montecuccoli, Carlotto, Elba, Vettor Pisani, Fieramosca, Caboto and Lepanto all visited Hong Kong. Benito Albino Mussolini, son of Benito Mussolini and Ida Dalser, visited Hong Kong while serving on a warship Quarto.

In 1925, Neapolitan pilot Francesco De Pinedo (1890 – 1933) landed his Savoia S-16ter two-seater hydroplane he had nicknamed Gennariello in the Hong Kong harbour. Engineer Ernesto Campanelli from Oristano was his co-pilot. After Hong Kong, they flew to Shanghai, Japan and Australia and then back to Rome, landing on the Tiber River. It was a truly remarkable expedition, considering that their seaplane had an open cockpit and that their only onboard instrument was a compass.

Amleto Vespa, a mercenary and secret agent from L’Aquila, also travelled through Hong Kong. In his book Secret Agent of Japan, published in Great Britain and the United States, Vespa unveiled a series of dirty tricks that the Japanese generals were planning on China. The Japanese did not appreciate this coverage, and shot Vespa in Shanghai in 1941 as soon as they were able to lay their hands on him. Ilario Fiore wrote a biography of Vespa using the scarce information available to him.

During the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, all Italian residents suffered considerable hardship. On 1 August 1942, the Italian Consul in Guangzhou reported:

The situation our civilian and missionary countrymen face in Hong Kong is dire.

The missionaries are too many, their numbers is high due to the influx of members of religious orders fleeing the mainland. Luckily there are only three civilians, two of which are here with their families. Beyond the current difficulties, which they try to face with bravery, our countrymen fear the uncertainty of the future and that ill-concealed hostility they see lurking in the eyes of the Colony’s new leaders [the Japanese]. The Mission’s financial situation is quite desperate. […] Monsignor Valtorta reports that the Mission may not draw, except temporarily and solely as a loan, from the funds sent by the Vatican, which are to be donated to charity or used to provide assistance to war prisoners, and not to maintain the Mission, as expressly stated by the Pope himself. Monsignor Valtorta, whom I found aged, emaciated and extremely nervous, has imposed stringent economic measures. He has set the maximum daily allowance for food for his missionaries to two Hong Kong Dollars per day. This amount, however, is far from sufficient for the purchase even just a daily ration of rice. Our Canossian Sisters face similar difficulties, and they are horrified at the thought of soon having to close their doors and leave behind over four hundred sheltered persons (invalids, blinds and children) to the mercy of God.

Only the Salesians did not request my assistance; indeed, their Father Superior told me that “luckily, they were in a very safe situation.”

The Japanese occupation of a number of their buildings did not cause them any inconvenience, and the careful administration for which their order is renowned, allows them to face the present crisis peacefully and without major concerns.

With regard to our three countrymen, Sasso Innocenzo, Lazzeri Sinibaldo and Guerci Giacomo, they managed to obtain permission to open and run a small but very decent trattoria, which they financed with the little cash they still had at their disposal. They scrape a living, waiting to recover their credits from hotels where they once worked or from the banks in which they deposited their funds. However, their situation is critical; I fear that if their claims remain unresolved, we will soon need to transfer them abroad.

WWII ended in Italy on April 29 1945, but Japan surrendered only on August 9th, 1945, then British forces were able to return to repossess their old colony. Prisoners of war were liberated and refugees from China and Macau returned to their half destroyed and impoverished houses. Americans intended to return Hong Kong to China but met with strong opposion from their British allies. Then, with the shifting power in the Far East, they did not push the matter, and wait how the struggle between the KMT (Kuomingtang of Chiang Kaishek) and the Communists would evolve. There were few Italians left, Oseo Acconci took a ferry in Macau back to Hong Kong and was met at the immigration by a stern British sergeant who knew him. He called on him to come forward and keeping his whip under his posed to him a puzzling question: “Acconci, you are Italian, right? if your government would have asked you to bomb us, would you have done that?”

Acconci replied: “Yes, of course!”

The sergeant then told him: “You are a brave man, Acconci, welcome back!”

The old colony gave another proof of his resilience springing back aided by a framework of good laws put in place by the British. In the early fifties, with the influx of capitals and men from Shanghai fleeing from the Communists, it became even more prosperous than it had been before the war.

Many famous Italian actors and directors visited Hong Kong, such as Federico Fellini – his niece still lives in Macau – Michelangelo Antonioni, Roberto Rossellini, Marcello Mastroianni and Sofia Loren – who had played the lead in Charlie Chaplin’s movie A Countess of Hong Kong alongside Marlon Brando.

Many renowned Italian conductors and soloists, such as Salvatore Accardo and Uto Ughi, also travelled to Hong Kong. Maestro Attilio Foa lived in Shanghai and then in Hong Kong. Mario Mio, a singer from Trieste, performed for three years at the Mistral, in Kowloon. The Acconci brothers are very famous in Asia, performing in a band known as the Soler. Paolo Borghese, the son of prince Junio Valerio Borghese, lived in Hong Kong for several years. A talented engineer, he designed many of the electrical infrastructures that supply energy to the city. Pietro Badoglio, grandson of General Badoglio, worked in Hong Kong in the clothing industry before his premature death.

After the Second World War, various Italian authors wrote about their visit to Hong Kong. Curzio Malaparte, an histrionic journalist and writer from Prato, who travelled through China. His journey was cut short, however, by an illness that later caused his death. He was so well cared by the Chinese that he decided to bequeath his villa in the isle of Capri to the People’s Republic of China, who still owns it

Several reporters for Italian newspapers travelled through Hong Kong and Macau: Goffredo Parise, Sergio Moravia and Enrico Emmanuelli, who titled his book, published in 1957, with the rhyme La Cina è vicina. Luigi Barzini Jr.; Renato Ferraro; Ilario Fiore; Carmen Lasorella and Tiziano Terzani, author of several books, including A Fortune-teller Told Me, partly set in Hong Kong: Terzani could often be found sitting at a table at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club, in what used to be the non-smoking room. Ennio Flaiano wrote a short story set in the Peninsula Hotel during a night of typhoon. Writer Vittorio G. Rossi set one of his books on sea travel, Festa delle lanterne (1960), in Hong Kong. Enzo Biagi visited Hong Kong and Macau several times, as journalist and as director of documentaries for the Italian television. Contemporary writer Cristina Cappa Legora lives in Hong Kong; she is the author of several fine art monographs and children’s books. Her latest one is: Storie della buonanotte per sogni coloratissimi, published in 2011. Marzia Orlandi is the author of Passaggio a sorpresa nel Porto dei Profumi, published in 2008. Paola Rondini wrote a detective story, I fiori di Hong Kong, 2010, also set in Hong Kong.

During the period that led to the Hong Kong’s handover to China (1 July 1997), in an effort to predict the British colony’s future, Hong Kong was a vastly discussed subject in Italy. But often analyses were influenced by the author’s political views. It was a chaotic time and a large number of Italian journalists were sent to cover the handover on location. Hence, they contributed to the practice later referred as “parachutes journalism”, a tongue-in-cheek term used to describe the practice of thrusting a correspondent into a geographical area to report on important historical events of which he knows close to nothing.

The Italian Chamber of Commerce is an institution increasingly successful representing the Italian business community. The Dante Alighieri Society of Hong Kong was already active in the ‘20 of the last century in Hong Kong, but closed down during the Second World War, it is a non profit organization which promotes Italian culture; the Hong Kong branch. It reopened in the ‘60, thanks to the commitment of Cav. Leo Li, now deceased. The Italian Women’s Association is a charity association which was chaired for several years by Anna Waung.

Eligio Oggionni every year organizes the annual Festa dell’Uva, which attracts an increasing number of participants who wish to spend one day in good company, eating good food and drinking good glass of wine. He had been also the founder of Scuola Alessandro Manzoni, which offer lessons for elementary and middle school students every Saturday morning.

Everything move fast in Hong Kong and Macau, everything changes quickly, rolls on, it is consumed, it is forgotten and, perhaps, this is as it should be because the old generation must leave space for the new generation.

I would like to remember here a few old friends who are no longer alive and cannot tell us their story. Angelo Pepe, one of the founder of the Italian Chamber of Commerce, a noble soul full of goodness and generosity. After him the presidency of the ICC was taken by Vincenzo Callà and Giovanni Orgera.

Luca Birindelli, a lawyer and a pioneer in Asia – his father was the famous Admiral of the Navy Gino Birindelli, gold medal in WWII. Franco di Vajo, from Varese, Hong Kong resided for more than twenty years and who was actively participating in and contributed to the life of the Italian community. Roberto Paggi, a visionary salesman and and industrialist, who saw the rise of China long before many other people. I apologize here for not mentioning all the others which would greatly deserve it.

The Diplomats

We are presenting for the first time a list with short biographies of the Italian Consular Representatives who took office in Hong Kong and Macau over the past years. Particular importance has been given to the representatives who served directly under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

This list is far from complete and it excludes individuals whose terms of office were shorter than one year (short regencies). Also some key information about some consuls are missing, we just hope that a more extensive and thorough research will be attempted in the future.

Nothing similar has ever been published before and because of its extraordinary historical value we have decided to include it in this volume, even if it is not complete.

Sometimes representatives were awarded consular patent letters for both Macau and Guangzhou, although residing in Hong Kong.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Kingdom of Sardinia had consular representations in both Guangzhou and Macau. Thomas Dent was nominated Consul of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1816. In 1824, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies appointed two British citizens: Alexander Robertson and Antonio G. Daniele, residents of Guangzhou and Macau respectively. This office, which was granted to them more as a favour than as an honorary position, was also like a kind of commodity to be traded in that it allowed them to operate outside the monopoly of the East India Company. They did not actually hold any specific duty or responsibility towards the State that had appointed them and the mandate of their appointment was, therefore, rather vague. It is even likely that the merchants themselves had solicited these appointments at the courts of Turin and Naples, offering a fee in exchange. The office of Consul in some cases was granted as a form of protection. For example, Propaganda Fide’s Swiss missionary Theodore Joset was appointed Consul of the Kingdom of Sardinia for Macau in 1840, with an agreement with the Holy See in order to allow to Joset the possibility of bypassing a series of restrictions imposed on his ministry by the Portuguese authorities of Macau. Anyway it did not help much, because he was duly harassed, just because he had switched to Hong Kong.

In 1857, Camillo Benso of Cavour decided to reinforce the Sabaudian (Kingdom of Sardinia) consular network. Acting upon the advice of Riccardo Manca di Vallombrosa, who had just returned from a journey to Far East Asia, it was resolved that a consular office should be opened in Shanghai rather than in Guangzhou. James Hogg, a British silk merchant, was duly appointed. The nomination was officialized only three years later, on 31st May 1860. Hogg held his office until 1868, when Lorenzo Vignale, a real diplomat, was sent to Shanghai.

1861-63: John Dent – Consul of Italy

John Dent, of Dent & Co.

Dent & Company was among the most powerful hong (firms) in China, together with Jardine, Matheson & Co. (honorary consuls of Denmark) and Russell & Co.

John Dent (1821 – 1892) was the grandson of Lancelot Dent, the latter being the brother of Thomas Edward Dent, founder of this eponymous company; he had resigned from the company in 1831. Lancelot Dent was primarily an opium merchant. Imperial government official Lin Tse-hsu issued a warrant for his arrest which triggered the first Opium War. It is believed that Lancelot Dent inspired James Clavell when he created the character of Tyler Brock, in his famous 1966 novel Tai-Pan then in 1986 made into the movie produced by The De Laurentiis Entartainment, with Joan Chen and Bryan Brown.

John Dent settled in Hong Kong in 1858 with the title of Consul of the Kingdom of Sardinia. In 1861, at the birth of the Kingdom of Italy, he was automatically awarded the office of Consul of Italy. His headquarters were located where we find today the Gloucester Tower, in Central.

1863-67: Francis Chomley – Consul

Francis Chomley was an employee of Dent & Co. In 1865 he was one of the founders of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Limited (HSBC).

1867-69: John Dent – Consul

In 1869, the Dent & Co. trading company, operating throughout Asia, went bankrupt in the wake of the collapse of The Over end, Gurney & Co., a discount bank based in London. The discount bank was known as the banker’s bank. Their competitor Jardine, Matheson & Co. learned of the disaster thanks to a scoop (their mail steamer carrying news from Calcutta arrived two hours earlier than the others) so they were able to rush to close their bank accounts and withdraw all their cash and silver bars before panic took hold of the Colony.

Dent & Co. was forced to shut its Hong Kong office and operate only by their headquarters in Shanghai but in a decidedly reduced scale of operation.

1869-72: M. William Keswick – Consul

William Keswick was born in 1834. Like the Jardine and the Dent families, he was of Scottish descent. His grandmother was the sister of William Jardine, the founder of Jardine, Matheson & Co. In 1870, he ceased dealing with opium and between 1874 and 1886 he became the major partner, or tai-pan, of Jardine, Matheson & Co. He was repeatedly elected member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council.

1872-75: John Samuel Gower – Consul

A partner of Jardine, Matheson & Co.

1875-79: Theophilus Gee Linstead – Consul

A former officer of the British Navy, Linstead was buried in the Protestant cemetery of Happy Valley, where his tombstone still stands. He was a partner at Hoggs & Co., whose founder had represented Italy in Shanghai. A staunch freemason, he was appointed District Grand Master. At that time, the Hong Kong Masonic Lodge was based in Zetland Road, in the Mid Levels. It still stands today, but on Kennedy Road N.1, while maintaining the original name of Zetland Hall.

1879-97: Domenico Musso – Consul General

A merchant from Palermo, he was already residing in Hong Kong for business reasons at the time of his appointment. Though his tombstone is still visible in the Catholic cemetery of Happy Valley, his remains have been moved to Italy. His son, Giuseppe Domenico Musso, wrote an extremely detailed book titled La Cina ed i cinesi: loro leggi e costumi, published in two tomes by Hoepli, Milan, in 1926. In 1886, Bernardino De Senna Fernandes was appointed Consul of Italy in Macau. He was a rich merchant and in 1891 he was awarded the title of Patron Member of the Associazione dei Benemeriti Italiani. His monument is still visible in the Jardim da Casa Garden of Macau.

1897-99: Ugo Nervegna – Consul

Merchant and owner of Nervegna & Co., located at 13 Praya Road Central, Hong Kong.

1899-1919: Eugenio Zanoni Volpicelli – Consul General

Eugenio Zanoni Volpicelli was the first professional diplomat sent from Italy. An interpreter, he acted as Consul between 1899 and 1901, when he was awarded letters patent as Consul General. Between 1916 and 1919 he resided permanently in Guangzhou. An excellent sinologist, he wrote several books translated into French and English: China-Japan War (1896); Pronunciation ancienne du Chinois (1898); Russia on the Pacific, and the Siberian Railway (1899). He also published several articles in important magazines of the time. For many years he was a true reference point for all Italians visiting China.

1919-20: Emilio Eles – Consul

In 1913 was Consul of Italy in Melbourne. In 1917 he made controversial plans, in agreement with the Australian Government, for the forced repatriation of Italian immigrants of military age to enrol them into the Italian army. A very dramatic story, not well known in Italy, but that could easily be made into a movie.

Following Elis’s departure from Hong Kong, between March 1920 and July 1921, Vice-Consuls Camillo Fumingly, Ugo Gonella (an architect who was admitted into the Architects Register of Hong Kong) and Ugo Galluzzi temporarily acted as Consuls. A certain Raul Galluzzi is documented as being employed by Sassoon & Co., but it is not known if he was in any way related to the Italian Consul.

1921-23: Luigi Petrucci – Consul

Luigi Petrucci was born in Grotte di Castro (Roma) in 1887. He earned a Law degree at the University of Rome in 1911. In 1914 he was nominated Attaché and assigned to Alexandria in Egypt. In 1918 he was assigned to Lugano, and in 1920 to Locarno, in Switzerland. Between July 1920 and February 1921 he was Consul General at Corfu. He was later assigned to Kobe (Japan), with the letters patent of Consul, and then to Hong Kong, where he acted as Consul. In 1923 he returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1925 he was sent to Belgrade and in 1927 to Geneva, as Secretary of the Italian Delegation to the 45th session of the Council of the League of Nation. In 1929 he was moved to Warsaw and was later appointed Consul General in Ottawa in 1932.

Vice-Consul Giuseppe Biondelli acted as Consul between January and October 1923 he

was born at Pesaro in 1890. He earned a degree in Diplomatic-Consular Sciences at the University of Venice in 1919. He began his service at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1920, and was nominated Vice-Consul in 1921. In 1922 he was sent to Shanghai and in 1923 in Hong Kong where he acted as Consul General. He returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1924, and was nominated Secretary of the Italian Delegation for the signing of the Pact of Locarno of 1925. In 1926, he was first sent to the Principality of Monaco and then nominated Secretary of the Italian Delegation to the 7th Assembly of the League of Nation in Geneva. In 1928 he was moved to Liverpool with the letters patent of Consul General, and then to Berlin in 1932 with the same position. In 1936 he was transferred to London.

1923-28: Stefano Carrara – Consul General

In 1912 Consul at Malta.

Former Ambassador of Santo Domingo, Mexico, Chicago and Damascus.

After Hong Kong he was nominated Consul at Gibraltar.

1928-29: Alfredo Baistrocchi – Consul General

Admiral of the navy Alfredo Baistrocchi was the grandfather of Massimo Baistrocchi, who was also Consul General of Hong Kong between 1988 and 1991. In July 1929, Arturo Maffei was nominated Consul General of Hong Kong. Maffei never took charge of his office, and in March 1930 Emilio Manfredi was nominated to that position in his stead. During the period of vacancy, Ugo Gonella, first, and Luigi de Dionigi, later, acted as Consuls.

1930-31: Emilio Manfredi – Consul General

Emilio Manfredi had previously served in Buenos Aires and Chicago.

1931-32: Raffaele Ferrajolo – Acting as Consul

A Chinese interpreter, acted as Consul for just over one year.

1932-36: Alberto Bianconi – Consul General

Alberto Bianconi was the author of an essay on the neutrality pact between the Soviet Union and Japan, published in 1941.

1936-37: Arturo Maffei – Acting as Consul

In 1920 he ad been consul at Aden.

1937-40: Gennaro Pagano di Melito – Acting as Consul

Captain of the Navy, Gennaro Pagano di Melito was decorated during WWI. He was a captain of the navy patrolling the Adriatic. He was also the author of several popular books before the WWII: La nave pirata (1933), Mine e spie and Il principe marinaro (1934). Consul in Shanghai until 1941, in 1943 refused to join the RSI (Italian Social Republic) and was interned by the Japanese. He died in mysterious circumstances in 1944 near Beijing, while prisoner of the Japanese Army.

1940-41: Herbert Ros – Acting as Consul

Interpreter acting as Consul until China declared war on Italy in December 1941. Author of the book It is so nice to remember. Recollections of an Italian Diplomat (New York, 1972).

THE WAR YEARS.

On 10 June 1940 Italy declared war on Great Britain and France. Italians in Hong Kong were promptly arrested by the British and sent to concentration camps in India. Only those who had managed to escape to Macau and China were able to avoid deportation. With the Japanese invasion, on the 8th of December 1941, however, the situation reversed. Between 1942 and 1950 the Italian diplomatic office in Hong Kong and Macau remained closed.

1950-54: Eric Vio – Consul General

Eric Vio was born in Fiume in 1910, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He earned a degree in medicine at the University of Rome in 1933, and in 1936 he left Europe for Japan with a research grant. In 1937 he moved to Shanghai, where he was a surgeon at the General Hospital. Between 1943 and 1945, he was interned by the Japanese in the province of Shandong. Between 1945 and 1974 he worked in Hong Kong, and then moved to South Africa and finally to Taitung (Taiwan), where he worked at the Mission Hospital. He wrote numerous poetry books in Italian, English and German and was also a fine oriental art collector. Pieces of his collection have been auctioned at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, selling at extremely high bids. He married the famous pianist Maria Grazia Taddei, who lived in Hong Kong for thirty years. She was born in 1918, and died in Rome in April 2011.

1953 – 1960 Giuliano Bertuccioli – Consul General

A fine Orientalist and one of the most renowned Italian sinologists, Giuliano Bertuccioli was born in 1923. He joined the diplomatic service in 1952 as interpreter at the Italian Embassy in Beijing. There exists an amusing account regarding his misinterpretation of the ruling against a fellow Italian, who had been sentenced to death by the Chinese authorities. Bertuccioli had wrongly translated that the prisoner had been acquitted, informing Rome by cable of the judgement. As Chinese authorities were about to fire on the condemned man, Bertuccioli confessed his mistake and the Chinese, not wanting him to lose face, overturned the sentence and set free the Italian man. Bertuccioli often recalled this mistranslation of his youth with great pleasure!

In 1953 he landed in Hong Kong as Vice-Consul and was later confirmed Consul. Bertuccioli was fluent in both Chinese and Japanese. Between 1960 and 1962, he was President of the Oriental Department of the Giorgio Cini Foundation in Venice. In 1962 he was sent to Tokyo, where he remained six years. He alternated diplomatic service and teaching. In 1966 he was Ambassador in South Korea, and then Vietnam and the Philippines. He wrote numerous books and articles on the Far East. Died in 2002.

1954-56: Guido Relli – Consul General

Guido Relli (his real name was Guido Kreglich) was from Trieste. At the outbreak of the First World War, at the age of 17 was by pure chance in Russia on a ship. Because he was an Austro-Hungarian citizen, he was interned in Siberia until the end of the conflict. There he learned to speak Russian, German, English and French fluently. This was the beginning of his relationship with Russia, which lasted for all his diplomatic career. He spent many years at the Embassy of Italy in Moscow as an interpreter, and personally witnessed numerous dramatic events, including the Stalin’s purges and the Axis Powers’ attack against the Soviet Union. Sergio Romano in an article dated 22 February 2006 for the Corriere della Sera wrote:

Guido Relli, an Italian diplomat, recounted his memories to Ferdinando Mezzetti in a book published by Greco e Greco (Fascio e Martello, 1997). He reported that Marshall Tuchacevskij visited the Italian Embassy in Moscow in 1936 to attend the projection of a movie on the military operations against the Negus’s army. He watched with extreme interest and congratulated the Ambassador and the Military Attaché. The relations cooled down, understandably, during the years of the Spanish civil war. In the summer of 1940, however, the Foreign Minister Molotov proposed to Italy a treaty in which the Black Sea would be divided between Italy and the Soviet Union, much like the treaty signed between the Soviet Union and Germany in August 1939 for Poland and the Baltic Sea. Such meetings and agreements were based on the assumption that Italy and the Soviet Union had valid economic and political issues to become partners. Although it might seem a paradox, it can perhaps be said that the two countries shared a mutual attraction. Left-wing Fascism expressed some sympathy for the USSR, while Moscow showed a certain curiosity for Mussolini’s regime.

Guido Relli’s book, to which Romano refers, reads like a novel because Relli led a peculiar and adventurous life. In 1946, he personally had the chance to protest with the American Secretary of State, James Byrnes, for the treatment reserved to his native city, Trieste. Byrnes answered: “My dear young man – Relli was 50 at that time – what you say is true, but you forget one thing. Our boys must absolutely come home after such a horrible war. All our decisions stem from this.”

1956-59: Adalberto Figarolo di Gropello – Consul General

He had been Ambassador in Afghanistan, Norway and Switzerland.

1959-60: Filippo Muzi Falconi – Consul General

Member of an old aristocratic family.

1960-63: Piero Guadagnini – Consul General

Piero Guadagnini was a great diplomat and a man of high culture and manners. Below, Sergio Romano, former Ambassador turned historian and columnist, explains how, in an interview he gave a few years ago, he decided to enter thye diplomatic service:

I was a journalist, and I had no intention of changing profession. But people have no control on their destiny. I met the Italian Consul General of Chicago, Piero Guadagnini, a man from whom I thought I should take example. He convinced me to take the diplomatic entry exam. I did, and I passed it.

1963-69: Luigi Bolla – Consul General

Luigi Bolla was born in Càrcare, Savona, in 1910. He began his diplomatic career in 1939, and was sent to Alexandria of Egypt, Biserta and then to Berlin. During the RSI (Social Republic of Italy) he was Secretary of Serafino Mazzolini, Deputy Foreign Minister. After WWII he was arrested and tried but freed. Though “purged” he was able to start again his diplomatic career in 1949. He was sent to Brazil, Egypt and Syria. His diary, Perché a Salò, diario della Repubblica Sociale Italiana, edited by Giordano Bruno Guerri, was published by Bompiani in 1982. It is a book of extreme historical worth, it explains how an anti-fascist, as he indeed he had been, could accept to collaborate with Mussolini’s regime to the very end.

1969-71: Marcello Mochi – Consul General

Marcello Mochi was head of the III Office of International Cultural Relations and was a renowned expert and collector of Chinese stamps

Author of A journey of an Italian diplomat around Saudi Arabia in 1941, reprinted in 2003, by Al-Turah, Ryad.

1971-76: Pio Saverio Pignatti Morano di Custoza – Consul General

Pignatti Morano di Custoza is a member of an aristocratic family from Modena, which provided, and is still providing, valid public servants to Italy. Their aristocratic motto is: “We are noble by deeds and not noble by birth.” Villa Pignatti was bought by tenor Luciano Pavarotti; his widow still lives there.

1976-80: Michelangelo Pisani Massamormile – Consul General

Michelangelo Pisani Massamormile was born in Naples. He is remembered as a man of great culture and exquisite civility. He had arrived in Hong Kong just over a week before the death of Mao Zedong. A lawyer, he was a pupil of the great criminal lawyer Alfredo De rsico. He served in Grenoble, Israel and hile, but Turkey was the country he most treasured. He is friend of the President of Italy, Giorgio Napolitano.

1980-84: Raffaele Berlenghi – Consul General

Raffaele Berlenghi was born in Milan in 1940. He earned a Law degree at the University of Milan in 1964, and joined the diplomatic service in 1965. After serving at the Directorate General for Emigration, Berlenghi was appointed to the Special Diplomatic Delegation for Disarmament, Geneva, in 1968. He then returned to Rome to serve with the Directorate General for Political Affairs, the Cabinet of the Minister of Foreign Affairs and the Directorate General for Personnel.

Between 1970 and 1972, he served as First Secretary to the Permanent Mission of Italy for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in Paris, and later as Consul in Bastia. In 1975, he was appointed Consul of Warsaw.

In 1978 he returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where he was assigned to the Directorate General for Personnel and Administration. Between 1980 and 1984 he was Consul General in Hong Kong and, later, First Counselor to the Permanent Representation of Italy to NATO, Brussels. Then ambassador of Italy to Vienna.

He returned to Rome in 1988, where he served with the Directorate General for Personnel and Administration. In the same year, Berlenghi was promoted to Minister Plenipotentiary. In 1992, he was appointed Ambassador to Damascus. In 1997, he returned to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where was assigned to the Internal Control Service. Since 2000, he has served as Chief of the Permanent Mission of Italy to the United Nations in Rome.

1984-88: Gabriele Menegatti – Consul General

Ambassador of Italy to Beijing.

Born in Bologna on 28 November 1939, Menegatti earned a Law degree at the University of Bologna in 1963, and joined the diplomatic service in 1965.

After serving with the Directorate General for Personnel, between 1968 and 1970 he was appointed Vice-Consul of Hong Kong, posted at the Italian Trade Commission Representation in Beijing, where, in 1971, he was appointed First Secretary. In 1972, he became First Secretary at the Permanent Mission of Italy to the United Nations, New York, and in 1975, served as Chargé d’Affaires ad interim in Hanoi, where he remained as Counselor until 1977.

Upon his return to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he served with the Directorate General of Personnel and Administration until 1984, when he was appointed Consul General for Hong Kong. Between 1988 and 1990, he returned to the Directorate General of Personnel and Administration, and in 1990 he was appointed Ambassador to New Delhi.

In 1995, he became Chief of the Press and Institutional Communication Service of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1996, Menegatti was appointed Interdirectional Coordinator for Asia and Oceania. In 1999 he was nominated Ambassador to Tokyo, and in 2001 he was promoted to the status of Ambassador of Grade 1.

1988-91: Massimo Baistrocchi – Consul General

Massimo Baistrocchi was the son of Ettore Baistrocchi, from Livorno, who was Consul in Japan. On 8 September 1943, Ettore Baistrocchi chose to side with the King and was interned with his family in a concentration camp in Japan until 1945. At that time, Massimo Baistrocchi was only 16 months old. Baistrocchi is the author of many books and articles, the last Ettore Baistrocchi, mio padre Rubbettino, 2008.

He died in Namibia on 22 January 2012 of a heart attack. Old residents remember him for his pipe, for his passions for Italian cuisine and painting, more than anything else.

1991-96: Folco De Luca Gabrielli – Consul General

Folco de Luca Gabrielli was born in Rome on 6 September 1947. He earned a Law degree at the University of Milan in April 1971. After passing the diplomatic entry exam, he served at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as Secretary of Legation in March 1975.

In 1977 he was assigned to the Private Secretary’s office of the Under-Secretary of State. In 1978 he was appointed Second Secretary for Social Affairs at the Permanent Representation of Italy to the International Organizations in Geneva, where he was promoted First Secretary of Legation in 1979.

He served as First Commercial Secretary in the Embassies of Italy at Kampala in 1981 and Teheran in 1983. He was promoted Counselor of Legation in 1984, and confirmed Commercial Counselor in Teheran until 1986.

After being promoted Embassy Counselor, he was nominated Consul General for Hong Kong and Macau on 26 October 1991. In August 1996 he was nominated Consul General for Los Angeles. In October 1999 he returned to Rome and in 2001 he was outposted to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers. In 2003 he was promoted Minister Plenipotentiary. He was Ambassador to Singapore between February 2005 and January 2010, when he was nominated Ambassador to Kuala Lumpur. In July 2012 he returned to Rome. He is currently serving at the General Inspector’s office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

1996-98: Alberto Bradanini – Consul General

Alberto Bradanini was born on 9 July 1950 in Rome, where he earned a Political Science degree in July 1974.

In August 1975 he joined the diplomatic service, with a specialisation in social services. In 1978 he was assigned to the General Headquarters for Emigration and Social Affairs, and in 1978 he was appointed Vice-Consul at Mons.

In 1980 he was promoted First Secretary of Legation and a year later he was assigned to Caracas. In 1983 he was transferred to Oslo, where he was confirmed Counselor of Legation two years later. He returned to Rome in 1986 to serve with the Directorate General of Personnel. He was promoted Embassy Counselor in January 1991, and, in August of the same year, First Commercial Counselor at the important Embassy of Italy to Beijing. In August 1996 he was nominated Consul General to Hong Kong and Macau. In February 1998, he was outplaced to the United Nations Office at Vienna, as Special Assistant of the General Director, and, from 1999, as Director of the UNICRI (United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute) at Turin. In 2003, he was promoted Minister Plenipotentiary. In January 2004 he was assigned to the General Director’s Office for the Mediterranean and Middle East Countries. On 15 April 2004, he was assigned to the General Directorate of Asia, Oceania, the Pacific and Antarctica, as Head of the Italy-China Governmental Committee.

After assisting the Director General for Multilateral Economic and Financial Co-operation, in January 2007 he worked temporarily at ENEL (Italian National Electricity Board). In August 2008, he was appointed Ambassador to Teheran, and in the summer of 2012 Ambassador to Beijing.